It seems like every new remix of Karl Fisch's "Did You Know" gets better and better and the message is made more and more clear. This latest version from Tom Woodward and Jim Coe (check out their Bionicteaching blog) which I pulled off of TeacherTube is great.

Thursday, March 29, 2007

Remixed Versions

Posted by

Unknown

at

1:47 PM

![]()

Labels: didyouknow, school 2.0, schoolreform

Wednesday, March 28, 2007

When We are Ready, and No Sooner

I can't think of any model other than networks that is capable ofWhat pressure do educators/administrators feel to move away from traditional methods towards blogging as professional practice? It's the whole horse and water thing here. We have to find something to make our staff not want, but need to buy into this. Right now, there is no tipping point in sight, but I think Siemens, and Stephen Downes, as well as a host of others, are spreading the word about the value of learning networks that include blogging and other forms of informal learning mixed with formal classrooms.

adjusting and reacting at the required pace and manner. But the real

problem is not identifying the solution to our current challenges. The

real problem rests in implementation. When we move to networks, we need to change pretty much everything else. It's like a software program

that has been written in one language, and we are now trying to write

it in another. We can't simply add on and tweak. In education, we

basically have to start over...rethinking curriculum, teaching,

learning, the role of technology, and so on. I don't think we are under

enough pressure yet to make changes of that scale.

Technorati Tags: networks, connectivism, blogging, siemens, downes

Posted by

Unknown

at

11:06 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: blog, connectivism, networking

Benefits of Blogging

meaning how to post a comment and what to do with all of the bells and

whistles on the sides. One of the goals I have set for myself this year

is to try to introduce more free technologies that are available

through the web, and to show the benefits of them to us as

professionals. Whether they translate directly into classroom use is

not really the big concern here, but rather how we use these tools to

make ourselves better researchers, better learners, and thus better

teachers.

In researching this and finding various applications,

I can't help but keep coming across the issue of blogging as

professional development and professional practice. I wanted to share

this quote from Christine Hunewell's blog which comes from a post

titled "A Blogger as a Writer:"

Usually I post late in the evening, just before the end of my day.As

Throughout the day, I think about an idea, a notion, the content of the

day’s post. I find myself composing phrases at odd times. If I come up

with something I really like, I often make a note to myself. I even

started a running list of ideas about which to post - old stories and

memories, things that are on my mind, that sort of thing. When I

finally do sit down to blog, I have my dictionary application open so I

can check spelling and reference the thesaurus. I compose the day’s

post, then I reread and revise. Mull over my choices of words. Vary my

sentence structure. Make sure the paragraph flows. Try to be concise

but clear. I work hard on the ending trying for a big finish. When I

think I’ve got it right, I publish - and then shut down for the night.

But in the morning with coffee, after I’ve caught up on the news, after

I’ve checked email and the weather, I read the post again. If it needs

tweaking, I do it then. I find it helps in the revision process to have

that little bit of distance from the original writing session.

you read this, what did you think of? For me, it was the fact that this

is exactly what we try to instill in our students as writers and as

thinkers. One of the key ingredients to higher-level thinking skills is

the ability to revise and create anew. Hunewell's experience's show

this as a natural facet of the process of blogging.

There are two levels to think about here:

- Blogging

as a professional practice enables you to reflect on your craft and

your methods, but it also provides you with an audience to provide you

with feedback. - Student blogging is an idea that we can

pursue. If reflection and writing for a wide audience is something that

we want our students to experience in order to make them better

writers, could this not be an option that might take them to the next

level?

safety of student blogs, but new, education specific blogging portals

are available with various levels of security. Places like 21Classes are prime examples of this. Also, if you have time, reading Christine

Hunewell's entire post is worth it.

A version of this post was also published at the Tech Dossier.

Technorati Tags: blogging, writing, education, students

Posted by

Unknown

at

3:49 PM

0

comments

![]()

The Death of the Term Paper?

...the old-fashioned term paper -- composed by sweating students on aThis is from Jason Johnson's op-ed piece in the Washington Post on Sunday. I think it speaks volumes about what we call school reform and the entrenched systems that are going to change.

typewriter as they sat elbow-deep in reference books -- has no useful

heir in the digital age. It's time for schools and educators to

recognize the truth: The term paper is dead.

The article is titled "Cut and Paste is a Skill, Too." Right there, he captivates. In working with both teachers and students, this might be the number one concern about switching to Web 2.0 applications: how do I stop them from plagiarizing? Johnson says we might not be able to.

Internet plagiarism is growing at a rapid pace, according to recentWithin the article, Johnson makes reference to the fact that not only are students turning to term paper services like StudentOfFortune for term papers, but for homework answers as well, with that transaction cost being $1 per answer. The culture of sharing through social networking is being taken to a new level by students of today. Should educators be discouraging this transfer? Or should we reevaluate what we are asking students to do?

studies and the anecdotal evidence I hear from my former colleagues in

education -- and there's no end in sight.

The larger question here is what does this tell us about today's student? If it's possible to tear ourselves away from our own school experience and focus on the skills necessary for success in today's world, what does this tell us about the relevance of things like term papers? I will not go as far as Johnson, yet, to call for the death of the term paper; however, this is a topic worth looking into when we begin to redesign our schools. It was even more telling to look at the comments left by readers of the article. One commenter noted that to copy and paste one source makes you a plagiarizer, but to copy and paste many sources makes you a scholar.

Nevertheless, the educational system needs to acknowledge what theDoes the ability to synthesize information from disparate sources into one continuous form have merit in today's world? Absolutely. However, the assessment aspect of the "term paper" should never be ignored. What are our new options? I foresee a shift from the term paper that stresses large-scale research, utilizing various sources, visualizing data in multiple ways, and finishing with a demonstration of tangible learning by either presentation in an oral way, or through a rich, multi-media design. Johnson makes a key point about the relationship between how most schools assess term papers that "cut and paste" and about what they may show regarding student learning:

paper is today: more of a work product that tests very particular

skills -- the ability to synthesize and properly cite the work of

others -- and not students' knowledge, originality and overall ability.

Students who are able to create convincing amalgamations have gained aServices like TurnItIn.com, and Google searches with large chunks of student writing feel more like band-aids at the moment, and it's only a matter of time before students figure out how to get around those measures (if they haven't already). Instead of being reactionary, let's jump ahead of the curve and re-design our idea of the research paper to incorporate this amalgamation that Johnson talks about.

valuable business skill. Unfortunately, most schools fail to recognize

that any skills have been used at all, and an entire paper can be

discarded because of a few lines repeated from another source without

quotation marks.

Technorati Tags: research, school, reform, termpaper,

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:52 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: research, school 2.0, schoolreform, termpaper

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

Trepidation

The schedule of classes I am teaching has truly gone insane over the last few days. I will be teaching 5 different workshops over 8 days, most dealing with Web 2.0 technologies, but some others with Adobe products. Currently I am in the midst of a two-day wiki workshop with middle and elementary teachers. Here is the link to the wiki I am using.

Yesterday was the first day, and I spent most of the time showing them student reactions and the pedagogical advantages of using a wiki with a group of students. The benefit that is most important to me, and which the group echoed, was that of being able to scaffold at an earlier stage, especially with projects. For example, plagiarism is a major problem area for us here, and heading off a potential instance of plagiarism is much easier when you have access to the student work as it is being created on the wiki. That resonated with the my class yesterday immediately.

One thing I find, and I hear several people in the blogosphere talk about this, is that idea of using technology for the sake of using it. Several of the teachers I work with ask questions like: what is different about using this than what I already do?

The answer, usually, is nothing. It's rare that there is a teacher who sees an application and immediately understands the possibilities it possesses. We often try to take new technologies and use old ideas with them. I can't fault people for doing that; it is a natural process. We understand and assimilate information into our networks by testing it with things we already know how to do. I understand we are in the early stages of the LOTI adoption scale here, but it is a fine line I am walking between overwhelming people and helping them use some these great applications.

This might seem like a common topic with me, but I want to be sure that I don't fall off this line.

Technorati Tags: wiki, edtech, blogosphere

Thursday, March 22, 2007

The Key Ingredient in a Collaborative Writer

A couple of days ago, George Siemens posted about Coventi Pages and it's unique way of showing edits and comments as a sidebar, which makes for great editing and collaboration. What I like about Zoho's product, first off is the prettiness of Zoho and the whole suite of apps, and now they just announced that their will be a chat feature added to their Zoho Writer. This is a good thing for anyone who has worked with either Zoho or Google Documents.

I could never figure out why Google Spreadsheets had a chat feature, but Docs did not. In my opinion, the chat feature should be a standard on any collaborative editing package out there.

This post also brought up another problem for me when I looked at it in terms of what is available in this area of Web 2.0. As more of my staff are beginning to see the possibilities of lesson design that utilizes Web 2.0, they are not ready to deal with the onslaught of choices. As a tech coordinator, I try to steer them in a direction that I think will minimize confusion, frustration or data loss. That decision often has a lot to do with what is recognizable to the user.

Branding is important. As someone who is actively involved in finding better options for teachers to use to create lessons, integrate technology and design curriculum, this is something I run into all of the time. A brand carries a lot of weight with people, often at the expense of functionality and efficiency. However, where is the line between what the teacher feels comfortable with and what is the more efficient product? This is where apps like Coventi and Zoho might struggle. Schools, like all other businesses, have been the victims of so many fly-by-night technology companies that have sold them something cutting-edge, only to have that bite them in the proverbial arse shortly thereafter. A solid brand like Google, though completely functional and usable in the online writing application genre, will win out among casual users every time because it is a recognizable name that isn't going anywhere. With that comes an illusion of accountability to the user that is yet another feature that draws the user to their product.

So, while Zoho and Coventi's products show promise, and in my opinion contain better features than Google Docs, I will be hard pressed to sell the use of Coventi or Zoho to my staff. That's OK, because I think this is a win-win situation; if we are using these collaborative pieces, that makes me happy.

Photo from Morguefile.

Sunday, March 18, 2007

Characteristics of Digital Natives

From Susan McLester's recent post at TechLearning:

Would this list look differently if it were created by a group of classroom teachers?Characteristics of a Digital Native

Following is a compilation of characteristics of 21st-century learners gleaned from a variety of sources, including an American Association of School Librarians blog, high school and university student interviews, and Kim Jones, vice president of global education for Sun Microsystems.

- Multimedia oriented

- Web-based

- Less fear of failure

- Instant gratification

- Impatient

- Nonlinear

- Multitasker

- Less textual, more modalities

- Active involvement

- Very creative

- Less structured

- Expressive

- Extremely social

- Need a sense of security that they are defining for and by themselves

- Egocentric

- Preference for electronic environments

- Have electronic friends

- Thrive with redefined structure

- Surface-oriented

- Information overload

- Widening gap to information access

- Share a common language

- Risk takers

- Technology is a need

- Aren't looking for the right answer

- Feel a sense of entitlement

- Constant engagement

- All information is equal

- No cultural distinctions (global)

- Striving to be independent

—with acknowledgment to Diane Beaman

Posted by

Unknown

at

8:11 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: digital natives

LectureFox and Freedom

As I prepare for the second week of my Web 2.0 class, I really want to stress to the teachers I am working with the importance of these type of sites, where people can have access to information that used to be considered scarce. I also want to let them see the role they may play in shaping the way students can access that information. It is not that we will be reduced to obsolescence, but rather our role will be to design and shape, and specialize in knowledge management.

If you get a chance, check out LectureFox. I don't normally get worked up about this type of stuff, and it slightly depresses me for financial reasons (pay scales in New Jersey for teachers are based on graduate credits earned), but this is some great stuff. Now you will have to excuse me, I am going to read up on my Buddhist Psychology.

Technorati Tags: opencourseware, lecturefox, web2.0

Image Credit: crimsondevotchka on Flickr

Posted by

Unknown

at

2:46 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: education, lecturefox, mit, opencourseware, web 2.0

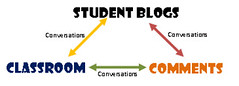

More on "Conversations"

In order to get some of these ideas going a little deeper, I will re-post Clay's comment on "Blogs as Conversations," here:

Think about the structures we have always placed on the writing process. We still use those structures, only the end piece is shifted dramatically. Audience is the most intriguing factor for us as teachers of writing because of the stress it places on the earlier steps of the writing process. Just by allowing for other students to access your writing openly and without the constraint of a 40 or 80 minute class period, it places new stress (what I would call "good stress") on the writer as he or she develops ideas, formulates syntax, and revises. Eliminating the time constraint that a student's work is open to others really transforms the whole process.

Professional development for students? I like that one, and our teachers will like to hear that as well.

Posted by

Unknown

at

12:35 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: burell, Edtech, professionaldevlopment, write, writingthecity

Friday, March 16, 2007

Changing the FBI

Here are a few samples:

People who know the FBI best--including many who've spent their careersAnd speaking directly of the human resources within the FBI:

there--would say that its culture, leadership philosophy, and links to

the political arena make major change in "the bureau," as it is also

known, highly improbable. It is, they argue, just too entrenched, too

bureaucratic, too rigid, too old, too slow to understand and execute

the scale and sweep of change that needs to happen.

It possesses impressive pools of talent, determination, tools, andIt looks to me that the large-scale change in any organization dependent on bureaucracy is more than just throwing laptops at employees or changing a policy. It looks like it's also a salesman's job. But it also draws positive comparisons when we look at the quality of the employees in the two professions.

dedication. But it tends to be a risk-averse, plodding, highly

politicized work environment with a bunker mentality that doesn't

easily absorb outside criticism and input.

Technorati Tags: fbi, schoolreform, IT

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:54 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: FBI, school 2.0

Thursday, March 15, 2007

Setting us on Fire

What’s your plan? We mean a real plan. Not just “kids learning independently on matters of personal interest, taking advantage of the power of digital technology to help them do so.” What will the structures look like? Policies? Laws? Funding streams? How will we know if kids have learned anything important? How will we handle parents’ very real needs for someone to take their kids while they go to work?It reminded me of being a sophomore in college, coming home and arguing about the state of the world with relatives, them being ultra-conservative, and me naturally being young and liberal. When pressed, I never could give them concrete evidence or a tangible plan of action on issues like universal health care or whatever it was at the time. This is the same call here; what cards are we holding?

Quit offering us wishes. Quit offering us dreams. Quit preaching to us about what is morally right and educationally appropriate. Help us realize, in terms we can understand, what this new thing might actually look like AT SCALE and how we might reasonably get here. Even if we agree with you that this is important, without a vision AND a plan we’re just as stuck as you are.

Most of us on the tech side are coming at this from a philosophical perspective, where we can see the value in these applications; however, more and more of the teachers I meet and listen to really want to know the nuts and bolts--how is school going to look and where is my place in it going to be? We talked about BHAG's for quite a while not too long ago. Would this not be the best of all? Let's make it actually have shape, and form, this idea of School 2.0. What are the standards that will be assessed? What will assessment mean in this new form? Are our physical structures going to look the same? Is the nature of instruction going to be so radically different that we have to tear down everything that has come before?

My take on Scott's piece is one of optimism. Let's answer real questions with real solutions that make sense to a broad spectrum of stakeholders. The community that supports a school may not have the time or the wherewithal to care about our methodology and the minutiae of what we talk about here in the edublogosphere, but they do care about the product and they do care about how it is created, because more often than not, they are the ones paying for it.

Technorati Tags: bhag, school, reform

powered by performancing firefox

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:48 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: bhag, mcleod, passion, schoolreform

Blogs as conversations

I was leading a group of teachers today through some of the basic facets of Web and School 2.0 (at least as I see them), and that point came up: How is blogging different than a journal or a bound notebook that they use as a record of their academic thoughts?

Aside from the obvious digital nature, here are a few key points I would use in that discussion:

- hyperlinks- the act of writing in a blog is the prime example of connective writing. When I speak to students about linking within a wiki or a blog, I often show them the difference between two paragraphs: one with hyperlinks and one without. I ask them what makes the one with hyperlinks so different? Invariably, they say it gives them options. Linking within a blog gives the reader opportunities to explore and formulate opinions based on the original source--a veritable virtual tour of the topic at hand.

- conversation- Jeff brings this up in his post as the main differing point between the two. The example I gave to the teachers I spoke with today was that last week I posted an appeal for opinions on what the most cogent points of Web 2.0 for teachers might be. The responses I received helped me shape the course that they were taking. I showed them my post, the responses, and the areas of the world from where the responses came. It's not monologue that teaches us, I told them, it's dialogue.

- Reflection in regards to audience- I cannot speak for the rest of the blogosphere, however, when I write posts for any of my blogs, I am keenly aware of my audience in how I organize my thoughts. When I read any material, because I blog, I digest in a way that leans toward reflection and creation of content. I need to speak about what my processes are, what the world at large thinks of the ideas I come across, and how I can learn from greater minds, or at least the collective mind. A journal with no interaction does not give me that.

You see the problem with blogs is we are not accustomed to conversations extending past 3 o’clock when the bell rings. We are not used to having conversations that include more than the 30 students in our class or can affect others in a different hemisphere.especially after hitting them with Karl Fisch's/Scott McLeod's "Did You Know" video. I think teachers understand the need for an extension of the learning environment outside of the classroom, I mean that is why homework was created.

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:15 AM

27

comments

![]()

Labels: blogs, connectivism, school 2.0, web 2.0

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

The End Result

Regardless of the issues of setting this up within an established school, it is undeniable that this is authentic learning. If the students, still responsible for all state-mandated curriculum, are asked to use their acquired skills toward some meaningful research and action of their own, the results would be multi-faceted in terms of community benefit. If schools are truly to be centers of community in the future, much as they have been historically, then projects like this must draw in the public and augment how it functions. How better to "democratize" a student than to ask him or her to add value to an existing democracy through a project that forces them to interact with that community?

The changes called for by many of us are evenly seen as very demanding of existing teachers; they are going to have to relearn, and as Alvin Toffler stated "the illiterate of the 21st Century will not be those who cannot read

and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn." Here is our option: create teacher advisors on the secondary level of American schools. Instead of having teachers patrol the halls for a period, or sit at an sign-in table, give them a group of students much like a graduate advisor would have. Here is the way to reach out and change the thinking regarding how we teach. Konrad Goglowski's post today speaks of creating passion-based conversations between students and teachers as the building block for restructuring our schools to get moving towards this whole idea of "2.0." Requiring this would also require teachers to enter meaningful conversations with students about their scope of research and enable teachers to connect the students with the experts that they need to in the local community and the world at large. Connectivity, anyone?

In putting all of this together, I have been reading Clay Burell's recent posts regarding what the role of blogging should be for students. Not being able to do it justice here, I recommend reading the whole string at his blog. When we force blogging upon students as a means of collecting homework, we could be setting ourselves up for some backlash, as that would not be self-directed learning, but just another "requirement." Clay's solution, and one that fits very nicely here, is that class blogs, run by the class instructor, should be subject and homework posting specific. However, each student blog should have a life of its own, a place for reflection. This is where the bulk of student reflection would take place, regardless of discipline:

If a student likes math, let him/her reflectively write, on a muchClay's idea that at the end of 4 years, the students would have experience, much as a professional writer would, in creating content that has value to them, and because of its connective nature, to others globally as well. I cannot imagine the value to the student that 4 years of reflective writing within the school atmosphere would have on them as they walk out of our schools.

higher order of thinking than getting the facts right, about math. And

keep writing. For months, a year, years. As that writing progresses,

those mentors--composed of a writing specialist and a subject-matter

specialist (e.g., English and math teacher)--would periodically

conference with the student about his/her exploratory, reflective

journal-journey down the math path.

Ten-to-one, that student will eventually write his/her way down all

sorts of side-paths into math history (cohort pulls a history teacher

in for a conference), biography ("Why did Descartes invent calculus in

the first place?" the blogger will one day wonder), science ("How does

calculus work in the practical world?"--and cohort maybe sets up a

Skype conference with an engineer from the real world to chat about

that), etc. On and on.

To end this rant, Warlick posted today about the nature of student work in "school 2.0" v. student work in "school 1.0:"

Many kids are now doing their work in blogs and wikis. They have readers and commenters. They are engaged in conversations about their work. They are invested in their work. The rest of our children work on work sheets that are seen only by their teachers. They have nothing invested in those pieces of paper.

Posted by

Unknown

at

12:27 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: blog, capstone, school 2.0, web 2.0

Saturday, March 10, 2007

An Appeal for Opinions

As it is Saturday, and I have a rare quiet moment in the house (boy is sleeping and my wife is at the dentist), I sat down to hammer out some content on the wiki for this week's workshops. Since it lent itself most to this format, I began putting together my resources for "Welcome to Web 2.0" and soon realized that there were too many directions to go in. And if I am feeling that way, how do I expect my teachers to feel when I begin talking to them on Thursday?

The class is broken into three, one-hour sessions, one-week apart, and I thought the best thing to do then was to separate the class into three sections: what is Web 2.0, RSS Feeds and using the web to work "for" you, and a student collaboration piece. Now, my question to the world at large is fairly simple and beautifully complex: based on those three categories, where do you think I should take them? Teachers: what would you want to be taught about Web 2.0 and its classroom uses or what has stuck with you from any workshops or formal training? Technologists: what do you think the most essential message is in terms of what teachers should see in order to connect to their students? Admins: What do you want your teachers to know?

I want the staff to walk out of the meeting not necessarily armed with a ready-made lesson for them to take to class, but with a little cognitive dissonance. They should be energized but slightly unsettled to the point that they email during the week, or post on the discussion board of the wiki because they want more clarity. Yet, I don't want to have them tune out the tech guy because I am talking over their heads.

Any feedback would be greatly appreciated.

Posted by

Unknown

at

3:38 PM

5

comments

![]()

Friday, March 9, 2007

Are Our Students Really Doing Anything Wrong?

Yesterday I had the privilege of working with four students in a 7th Grade Study Skills class, a daily class for each of our special education students that enables them to either work on academic work from their course-load, or to practice skills that will help make them better students. My plan yesterday was two-fold: I was going to show them how to effectively search using Google, where to find the resources and external links in Wikipedia, and how to use Grokker (my new favorite student search engine), and I was going to observe how they interacted with the web when faced with research problems.

After I walked them through the basics of searching using quotations, plus signs and minus signs, and discussed with them the merits of Wikipedia, and more specifically how to begin their research there, I let them wander through their intended research. The projects they were working on involved searching out specific features of a country, like climate or current events or economy. What I noticed was the ease with which they accepted what they saw as fact. If the students landed on pages that contained bulleted points or lots of "facts" organized in a coherent manner they were highly likely to assume them as truth, without questioning the validity of the source.

I stopped them and asked them some questions:

Me: How do you know if a page is worth using for research?

Them: If it comes from a good source?

Me: What is good source?

Them: Google, CNN, anything that pops up on Wikipedia.

I've been reading the Macarthur Foundation's Spotlight on Digital Media and Learning blog for the last few weeks and this quote from Alecia Marie Magnifico in response to student interviews after playing epistemic games for several weeks, struck me yesterday when I finally got to it. When asked about how they use the web:

They tell us about using web sources for school reports, for chatting, for playing games with their friends. They even report knowing that anyone with a webpage can publish opinions for the world to see. I wonder how much of this finding comes from the simple fact that young people don't often need to check or even understand their sources: textbooks and teachers are the authorities, and they must be believed (even memorized!) in order to get good grades.

Bingo. They were looking for the right answers, not looking to authentically learn. Has that skill been neglected in our test-mandate society (wink)? When asked to complete the project at hand, finding out facts and delivering them, what better way to do so then to gather them from known, seemingly credible sources and give them back for validation.

My teachers are wonderful, dedicated individuals, which I am sure most districts throughout the country would say. Authentic learning is hard to do, let alone teach. How do I begin helping them restructure the way they affect student learning? How do we teach students to question what is given to them in the classroom by way of learned critique? Most teachers might see that as an invitation to disorder and chaos. But consider this, again from Magnifico's post:

A teenager questioning commonly-held information would likely be perceived as antagonistic in many classrooms, although the same behavior would be rewarded for a researcher developing a new theory or a doctor treating a pernicious ailment. These divisions between school and working-world occupations have led several education theorists to label most classrooms as "inauthentic" - composed of facts to memorize and "test questions" to which teachers have set answers -It's this type of juxtaposition that has our teachers cast in a bad light. I cannot fault a teacher for being upset or hurt when told that their methods are out of date; I cannot hold them to the fire and tell them to change. What I can do is show them where their students are landing on traditional scales and measurements with regards to learning, not testing. It's as basic as Bloom's Taxonomy. Watching those students, with whom I had great conversations about what is good content and what is bad content, let me see just where we are and where we should head towards. It's on us, and we need to adapt.

rather than "authentic" explorations of complex issues that may not have absolute solutions.

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:52 AM

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, March 7, 2007

Workshop updates

The blog has been hugely successful with staff members, and for very simple reasons. First, it offers them a glimpse into classrooms that they might not normally see, especially at the high school where time is short and people are scattered. A quick post on a project or technology that another teacher employs is sometimes the spark that another needs to pull me in for a meeting and planning session. Secondly, it is offering them a quick glance into how quickly we can communicate an ideas and create buzz with a large number of people within a community. While we are still trying to get some interactivity going between the teachers on the blog, and while it is mainly me writing it currently, we are hoping to get some comments and some guest writers soon. Blogging is a funny word in education; most want to do it, but are strangely afraid of what it means. I hope this will show them how productive and thorough it makes us as professionals.

Posted by

Unknown

at

3:59 PM

0

comments

![]()

Friday, March 2, 2007

How Far is Too Far?

One of the many things I am learning this year, aside from more technological applications, is how to recognize when I am overwhelming people with information or ideas. As many of us know, learning is a messy thing, with spills and fits and starts a constant part of the process.

Here is my rule of thumb, when no one in the room can finish your sentence for you on a routine, recognizable topic, then you have lost them and better slow down and refresh. Teachers and administrators have one basic thing (among many others, of course) in common: shortage of time, and I always try to plan with that in mind when presenting to either group. However, that doesn't always translate to a well-executed presentation.

My problem is that I see so much possibility for integration RIGHT NOW with my staff. It's a sense of urgency caused by in short form, the coolness factor, but in long form by the need to completely redesign the way we present material to students. Our ability to access information is unparalleled compared to any other period of history, and yet we are teaching students to access information using methodology that, although it uses technology, is based on how we researched with Dewey Decimal and note cards. The life we were prepared for is not the life we will be preparing our children for; our methods should reflect that.

When I get moving like this in a faculty meeting, what I mistake for passion and urgency, some might mistake for lunacy or might just, like the high school students in today's earlier post, tune me out as that crazy tech guy. And this is where the bulk of my learning is taking place--in that moment. Because I am forced tor respond to an obvious overshoot. I am getting better and better, but there still is a lot of room for improvement.

Posted by

Unknown

at

11:05 PM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: administration, behavior, Edtech, integration, school 2.0

Student Choice

We have truly educated the creative side right out of our students. They don’t want to have to think about it, they just want to fulfill the requirement that is being asked of them and move on.Half-expecting them to eat fire in order to choose the digital story option, I was shocked to find that only about half of them are choosing that option, with the rest of them putting their timeline on posterboard. While the dynamic is slightly different than the one that Jeff talks about, I truly was shocked by the non-choice of technology.

Is that more with me? Guilt lies with me sometimes, and I often feel foolish at times, when a teacher I am working with points out that I am using technology just for the sake of technology. For instance, the age-old PowerPoint debate. What skill is being learned from a bad PowerPoint presenation? More often than not, though, what we are promoting has new relevance in our curriculum, and there is open debate that at this point, any use of new applications and technology can be construed as positive. The reactions I am getting lead me to ask one thing:

Are our students as reluctant to change as some of our teachers?

The sense that I was getting from the three classes that I was in was that I was pushing something that was either passe to them, or that I was giving them such shift from the regular expectations that I was being tuned out. I make it sound disheartening, but it wasn't at all. Rather, it has forced me to reflect on what exactly is the meaning of engaging to our students. It might be naive to think that giving them options that include technology will solve the problem of learner motivation.

As with everything we do, it comes down to the quality of the design of the project, lesson, or task that we present to the students. That, coupled with a truly captivating instructor, will work every time.

Wes Fryer's notes from Marco Torres' presentation at MACE offered some insight into faculty attitudes towards technology. He categorized them in three ways:

- "yes, ands"- the eager adopter

- "yes, buts"- the skeptical adopter

- "so whats" and "no ways"- the Luddite

powered by performancing firefox

Posted by

Unknown

at

6:52 PM

0

comments

![]()

Patrick, you really do nail the pedagogical affordances that, in my book, only blogging offers to developing student literacy--writing AND reading.

What I'm now experiencing with my own students is this: the idea of being writers is unsettling to them. After 9 years of schooling, they have only written homework and "schooly" writing assignments--have only been students, and never writers.

So they are resistant to this shift. They don't want to learn to be writers, because it's harder. It makes them find their own ideas, instead of hacking out some tired exercise based on ideas that Teacher prescribed to them.

So students have to be "professionally developed" as well as teachers into what the read-write web means for their learning. It's new to them too, and just as uncomfortable.

Which brings me back to your main point: the training I'm pushing on my students now is precisely what you highlight: reading with writing in mind; writing with an audience in mind; conversing with other writers and readers via comments; hyperlinking and connecting.

Some get it faster than others. All need to hear this: we know you've never been a writer, and we know you're a novice. We're forgiving that way. This is a long-term journey you're starting, so start where you are as a writer, and we'll take you as far as we can in the coming years. Trust that you'll grow.

That sort of thing. Enjoyed your post.